I've done Advent of Code every year since 2018, which is an advent calendar with programming puzzles instead of chocolates. The puzzles ramp up in difficulty the closer you get to Christmas, yet require little knowledge of math theorems or data structures beyond arrays. That accessibility was the main thing that drew me to AoC, compared to other sites with programming problems like LeetCode or Codeforces.

At first, I enjoyed using the puzzles to hone my Java/C++ skills, but in 2021 I decided to teach myself Haskell through AoC. Learning a functional programming language completely changed how I write code, and I never want to go back. I did 2023 in Clojure since I wanted to try a Lisp, and this year I decided to pick up Scala. I've found the general experience to be very friendly for learning new languages, due to the gradual difficulty curve and daily release of puzzles.

Below are some of my thoughts on the three languages.

Haskell

Haskell is a really old, academic language. It goes hard into category theory and purity, requiring you to wrangle an IO monad to even print anything to the screen or accept user input. I think I finally understand what the heck a monad is today, but it took years.

The interact function abstracts a lot of this away so I was able to get through AoC, but I wouldn't have been able to write any kind of interactive program. However, this strictness also forced me to really embrace the functional style, and I learned a lot.

Some of my favourite aspects:

- amazing type system + type inference

- pattern matching

- laziness by default

- partial application + currying of functions

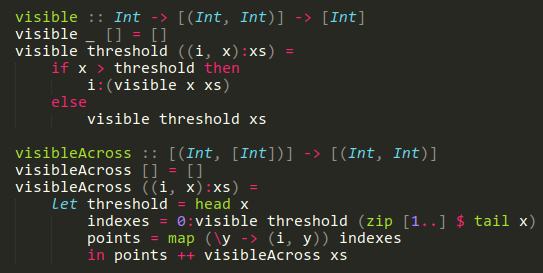

Part of 2022 day 8. It feels so elegant and clean. Not the easiest to read at a glance, though.

Clojure

Clojure is a Lisp, which means that it is composed of s-expressions. Those are either a literal or have the form (expr1 expr2 ...). No special syntax for function calls, if statements, or loops, but a lot of brackets.

One of the things I liked about Clojure was how easy it was to do things. For example, println just works wherever you want to put it. Imagine that, Haskell.

Another example is get/assoc, which allow accessing into and updating a structure respectively. For example, with a list of numbers, returning a new list where the 4th element is replaced with 7. Doing that in Haskell either requires really gross splitAt code or using a lens, whose documentation immediately jumps into Functors and Applicatives. I still have not used a lens to this day.

So many things that felt impenetrable in Haskell were very easy-to-use functions in Clojure. The core library also contains extremely useful functions like frequencies (creates a list of (item, # of instances) from a list), if-let (enters block if condition is truthy while binding a name to it), and memoize (makes a function cache results to calls), all of which I want in every programming language now. Clojure felt like the Python of functional languages.

However, Clojure is untyped. That led to a very significant amount of NullPointerExceptions and XX cannot be casted to YY, which was not fun to debug. (There's a library that introduces types, but I haven't looked into it much.) The bracket-heavy notation, while funny and not that hard to write, wasn't very friendly to read. I'd share my code with others and feel like I needed to constantly reorganize parts of the code to make it more understandable, even though my algorithm was quite simple.

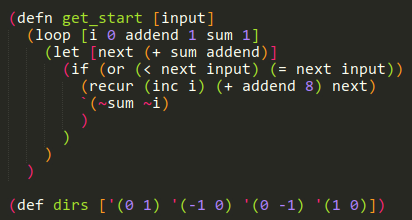

Part of 2022 day 3. You can tell what this is doing if you really try, but it just looks super intimidating.

Scala

I'd been recommended Scala quite a few years ago, when I was still writing Java. With my interest in functional languages, AoC 2024 seemed like a good time to try it. Scala is strongly typed, but it isn't lazy by default like Clojure or Haskell. It addresses some problems I had with both languages, but has its own quirks.

For one, there's a type system, but you sometimes need to curry a function's parameters for type inference to work.

val res = (0 until 100).foldRight(robots)((_, a) => a.map(_.update()))

Why does robots need to be separated into its own set of brackets, just so that the reducer function has the correct types inferred??

It's also hard to work with tuples, oddly. (1, 1) + (2, 2) doesn't work, and you can't map over them either. I've just extended Tuple2 with my own + function, but maybe I should be using a List?

Sadly, there's no partial/variadic application of functions. To illustrate what I mean, if I wanted to sum the numbers in a list,

- Clojure has

(defn sum [ns] (reduce + ns)) - Haskell has

sum xs = foldr (+) 0 xs

But in Scala, you need to write

def sum(ns: List[Int]) = ns.foldRight(0)(_ + _).

It's better than the JavaScript

const sum = (ns) => ns.reduce((a, c) => a + c, 0)

where you need actual dummy variable names, at least. But Scala's _ sugar isn't even as good as Clojure's anonymous functions like #(+ %1 %2) where you can reuse %1 mutliple times.

Unlike Haskell, you can println or insert IO side effects anywhere you want. And unlike Clojure, there are few brackets and no strange prefix notation. I find that the code is easy to read, and this is a huge benefit, because I read my own code a lot and also like to share it with others.

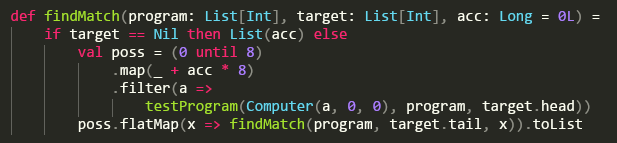

Part of 2024 day 17. It just looks familiar and comforting.

Conclusion

There's about a week left in this year's AoC, so I'll be getting a bit more practice with Scala and might have some new thoughts by the end. It's definitely not the perfect language for me, but it does feel very practical compared to Clojure and Haskell. I could definitely see myself writing a bigger program using it, which I failed to do in Haskell and had minimal success with in Clojure.

As for next year... I'm keeping my eyes open.